LOBO has spent much time and energy addressing pilot training in an effort to reduce the Lancair accident rate. I would like to focus on another area for a moment that has also contributed to numerous accidents and incidents in the Lancair fleet: Build deviation and Maintenance.

LOBO has spent much time and energy addressing pilot training in an effort to reduce the Lancair accident rate. I would like to focus on another area for a moment that has also contributed to numerous accidents and incidents in the Lancair fleet: Build deviation and Maintenance.

I have inspected a number of Lancair 320/360s over the years and have found numerous issues that could, and in some cases actually did, lead to an accident. What experimental aviation gives in freedom from the constraints of a production aircraft it takes away in the standardization of certified production lines, configuration control and tracking of service difficulties. As builders and owners of experimental aircraft we are free to deviate from the original Lancair plans and make changes during construction. When well thought out, these alterations can improve upon the original design in performance, usability, or maintainability.  For many, the kit and the assembly instructions as supplied were by no means optimal for individual purposes, but they provide a baseline that is known to work. Unfortunately without the proper engineering analysis and testing, changes made to the kit and/or assembly instructions can have very unpleasant unintended consequences. An additional complication arises when the aircraft changes hands. A new owner might assume the aircraft was built per original plans, and will almost certainly be unable to recognize alterations. In some cases the ‘alterations’ were not even an intentional redesign, but a misalignment, a missing part, or an incorrect bolt. Whatever the cause, deviations have caused damage and loss of life.

For many, the kit and the assembly instructions as supplied were by no means optimal for individual purposes, but they provide a baseline that is known to work. Unfortunately without the proper engineering analysis and testing, changes made to the kit and/or assembly instructions can have very unpleasant unintended consequences. An additional complication arises when the aircraft changes hands. A new owner might assume the aircraft was built per original plans, and will almost certainly be unable to recognize alterations. In some cases the ‘alterations’ were not even an intentional redesign, but a misalignment, a missing part, or an incorrect bolt. Whatever the cause, deviations have caused damage and loss of life.

A related drawback to the experimental freedoms we enjoy arises in the area of maintenance. We do not have the luxury of looking up maintenance manuals that specify wear limits and tolerances for components on the aircraft. The airworthiness is determined by the individual doing a particular inspection. The depth and detail of any given inspection is also at the discretion of the individual doing the work. Our condition inspection might mention Part 43, Appendix D as a guiding reference, but it's not very specific. For example:

(e) Each person performing an annual or 100-hour inspection shall inspect (where applicable) the following components of the landing gear group: (3) Linkages, trusses, and members—for undue or excessive wear fatigue, and distortion.

What exactly is undue or excessive wear fatigue and distortion? It is technically up to each individual owner to track the condition of every component of the aircraft. Relying on the A&P can provide a false sense of security unless that individual happens to be familiar with the specifics of a Lancair. A&Ps can, however, be a great resource for areas common to all GA aircraft such as engines, propellers and avionics.

Many mishaps blamed on a mechanical component failure can be tied to maintenance and/or construction in one way or another. In many cases owners are simply caught off-guard. They didn't know about a particular test, inspection, adjustment or service bulletin that was needed to ensure the continued sound operation of a system or component. They simply didn't know what they didn't know. Unfortunately there is no single data base that all can reference.

There have also been cases where the owner knew about a deficiency and chose not to investigate and correct the situation, or they simply put off a repair until it was too late. While continuing to fly with a known deficiency seems rather foolish, it unfortunately happens rather frequently. Ignoring an engine, electrical or landing gear issue has been shown to be quite costly. Prudence suggests warning signs should be addressed immediately, because the only policing mechanism is the consequences of part failure.

There have also been cases where the owner knew about a deficiency and chose not to investigate and correct the situation, or they simply put off a repair until it was too late. While continuing to fly with a known deficiency seems rather foolish, it unfortunately happens rather frequently. Ignoring an engine, electrical or landing gear issue has been shown to be quite costly. Prudence suggests warning signs should be addressed immediately, because the only policing mechanism is the consequences of part failure.

What follows is a list of some of the discrepancies I've found during inspections. Some of these items will seem rather obvious, while others are well hidden from view. Keep in mind that most items were on flying aircraft.

- Broken over center springs on main gear – no means of emergency gear extension

- Missing main gear re-enforcement – service letter not applied, gear later collapsed

- Missing primary wing to fuselage attach structure (this was on a flying aircraft!)

- No slosh bay and no header tank – risk of unporting during low fuel state

- No carburator heat on a carbureted installation – no defense against induction ice

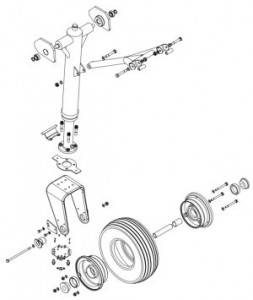

- Binding of landing gear linkage – misaligned bearing blocks

- Composite repairs that do not follow any industry recognized procedure

- Fuel pick-ups in incorrect location – unable to get to all the fuel

- Damaged spar caps – trimming wing skin went a little too far

- No hydraulic cylinder stops – over stressing over center links & cylinder attach point

- Play in trim tabs – can lead to flutter of the elevator and entire horizontal stabilizer

- Damaged nose gear gas strut – striking incorrectly installed bolt

- Deteriorating hydraulic hoses

- Abraded hydraulic lines – making contact with gear during retraction

- Corrosion inside flap torque tube

- Friction or binding in control linkages

- Construction debris found in fuel tank

- De-bonded trailing edges

- Mal-adjusted pressure switches – erratic gear operation

- Missing nose gear flange re-enforcement – back-up for Loctite

- Worn rudder bearings

- Wiring too close to moving parts in gear wells

- Worn control surface hinges

- Heat damaged wiring in engine compartment – too close to exhaust pipes

- Incorrect bolts in landing gear assembly – bolts too short

- Missing fire proofing of firewall

Education is the best means we have of making sure the Lancair fleet is in good working order. LOBO hopes to help you in that regard with posts on good maintenance practices here on our website.

Check the maintenance section often for updates!