What's Your Plan for 2019?

What's Your Plan for 2019?

by jeff edwards

2018 was a relatively “safe” year for the Lancair community, but we still suffered two fatal accidents. Sadly, we lost Angier Ames and his wife, Gynna, off Port St. Lucie on March 31st as they returned from the Bahamas in their 360. Weather may have been a factor, with radio transcripts indicating deviation for buildups. Additionally, Legacy owner/pilot, Dr. Robert Alberhasky was killed and pilot Mark Lewis was critically injured on November 18 in Gainesville, GA. The two were returning at night from Charleston, SC when they struck trees on a night VMC approach. While our safety record has greatly improved over the last ten years when we experienced twelve fatal accidents that year, we are reminded that even one fatal accident is too many.

Statistics

As some of you know, I have been a participant, representing LOBO, on the General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC) since 2011. When the GAJSC was reconstituted in 2011, the fatal GA accident rate stood at 1.1 fatal accidents per 100,000 flight hours. It had stubbornly remained there for nearly twenty years. Today the rate is 0.83, a nearly 25% decline. Here is a table from the FAA website reporting the U.S. GA fatal accident rates:

| Fatal Accidents/100k hours | Total Fatal Accidents | Total Fatalities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FY10 | 1.10 | 272 | 471 |

| FY11 | 1.12 | 278 | 469 |

| FY12 | 1.09 | 267 | 442 |

| FY13 | 1.11 | 259 | 446 |

| FY14 | 1.09 | 252 | 438 |

| FY15 | 0.99 | 238 | 384 |

| FY16 | 0.89 | 219 | 411 |

| FY17 (Est) | 0.84 | 209 | 347 |

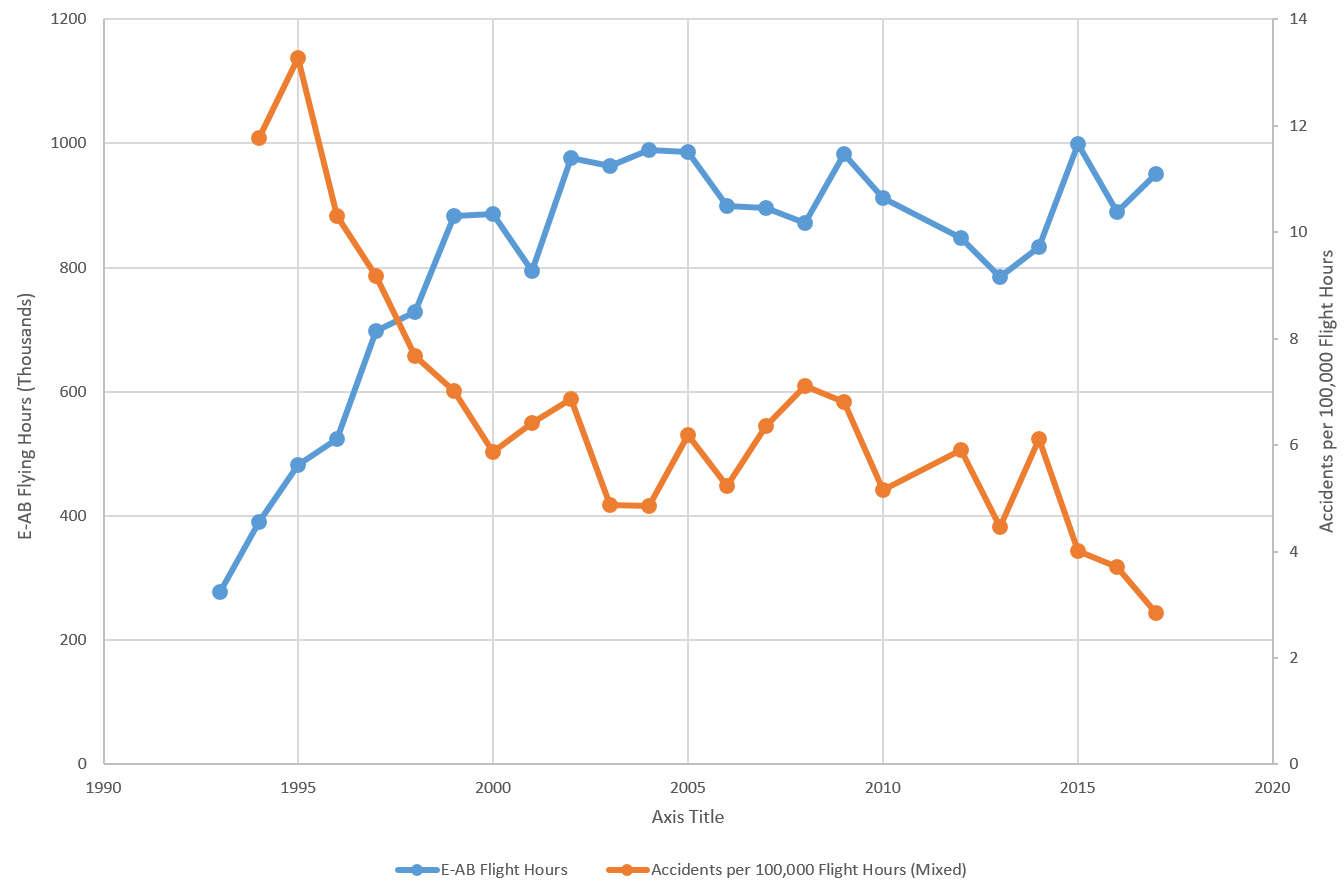

The experimental amateur built community is reporting similar success. EAA tracks the experimental category data as part of the GAJSC project. The chart below (credit, EAA Advocacy & Safety), from Tom Charpentier at EAA, shows the improvement in Experimental Amateur Built (EAB) aircraft safety; as flight hours have increased the number of accidents per 100,000 hours has decreased.

Can We Further Improve These Numbers?

Improving the accident rate takes hard work by everyone. We all should take this time of year to reflect on past flights and reevaluate our readiness for future flights. Just as Santa does every year, we should make sure our sleigh is airworthy, that all maintenance is performed properly, that all deferred maintenance is complete, and that our navigation databases include up-to-date data for flights from the North Pole (looking at you Bill Harrelson) to wherever we need to go.

We should also make certain of our own airworthiness. Some of us (you know who you are) might start with a few "push aways;" push away some of those cups of hot chocolate and plates of cookies. A visit to St. Nick’s flight surgeon might even be in order to keep us current with respect to aeromedical standards.

Finally, we should get out and practice our aeronautical skills with our favorite Elf flight instructor, who will make certain we can handle any emergency procedure that comes our way—up to and including a loss of a reindeer on takeoff. Make every flight this coming year your safest flight possible!

Orville and Wilbur Wright gave us the gift of flight 115 years ago. We should endeavor to pass it on to the next generation by demonstrating the joy of flight safely!

Incidents

Last month I was preparing our Lancair for a flight to Cincinnati to visit family for Christmas. The forecasts did not look promising—we were looking at snow and ice for the return trip on the day after the holiday. Just to be ready, my backup plan was to take the trip by car (ughhh!). In preparation, I put new tires on and had the vehicle in for its routine service, so I knew it was ready to go should the weather develop as forecast. I follow the same routine with the aircraft. Preflighted, topped off, oil checked, databases current, Foreflight current, etc. For my business trips I back up my Lancair flight plans with a refundable airline ticket so that I am under no self-induced pressure to go. Too often this time of year pilots fall prey to self-induced pressures to get there, sometimes with disastrous consequences for all concerned. Let's look at some examples.

Fuel Management

One such event happened on Jan. 2, 2015, in Kuttawa, KY. A family from Nashville, IL was returning from Florida in their Seneca. According to the report recently released, the NTSB identified pilot error as the cause of the crash. Killed in the accident were the pilot Marty Gutzler, 48; his wife, Kimberly Gutzler, 46; their daughter, Piper, 9; and a niece, Sierra Wilder, 14. The sole survivor of the crash was the Gutzler’s daughter, Sailor, who was 7 at the time of the incident. Sailor escaped the overturned cabin and walked away from the wreckage barefoot through a wooded area in the dark for about 20 minutes before finding help at a nearby home. The family took off after 3:00pm on the accident day—guaranteeing that the flight would end after dark. Additionally AIRMETS for IFR (low ceilings) and icing were issued. Even though the weather was poor, the cause of the accident was the simultaneous loss of power on both engines, attributed to the pilot placing one of the fuel selectors in the crossfeed position (probably during preflight) so that both engines were feeding off of one fuel tank. The night flight with a darkened cockpit likely led the pilot to not notice the mispositioned fuel selector. The NTSB also reported that the pilot skipped the before takeoff checklist where he might have caught the mispositioned fuel selector.

I have exercised Plan B several times in recent months due to weather. I have done my share of slogging through the weather, but I prefer to fly IFR in day, VMC conditions if at all possible, and I try to maximize my chances of VFR weather by adjusting my schedule when possible. Recently, I flew to south Florida for a week-long business trip. The flight down was clear-and-a-million, with a good tailwind. I finished work on a Thursday, but marginal weather and a later-than-anticipated departure led me to delay my trip home by one day. The next morning I flew home, refreshed, and in CAVU conditions. Perfect. Good risk management can improve your chances of getting safely to your destination. Flying single-pilot IFR in day, VMC conditions maximizes your chances of arriving safely with minimal stress. The IFR flight plan gets you the benefits of flying in the system (traffic separation, enroute advisories, etc.) while day, VMC operations allow you to see terrain, traffic, and avoid hazardous weather.

The Lancair community's two fatal accidents in 2018 involved weather (Lancair 360) or night operations hazards (Lancair Legacy). Get-home-itis, an unfamiliar aircraft and night operations can be a deadly combination.

Aeronautical Decision Making

On September 21st last year I woke up to news reports from our local TV station reporting on a fatal aircraft accident that had occurred the day before. I received many calls and texts that day asking if I knew what happened. A local airline captain (who was an acquaintance of one of my airport friends) and his teenage son took a commercial flight out of Saint Louis on the morning of September 20th with a plan to retrieve a Cessna 150 based in Collins, NY, and bring it to Festus, MO (KFES) the same day. According to the pilot's family, the airplane would be used for flight instruction for the pilot's son. The pilot worked professionally as a commercial airline pilot and previously as a helicopter air ambulance pilot. They departed from New York bound for Festus, MO at 1400 EDT.

The cross-country flight consisted of travel through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Receipts provided by a family member and found in the wreckage showed that the pilot had refueled the airplane three times during the trip. The first refueling stop was at the Chautauqua County/Dunkirk Airport (DKK), Dunkirk, New York, at 1434 EDT for 13.4 gallons of 100LL. The distance between the private airstrip in Collins, New York where the aircraft had been based, and DKK is about 19 miles. The second refueling stop was at the Knox County Airport (4I3), Mount Vernon, Ohio, at 1753 EDT for 16.56 gallons of 100LL. The distance between DKK and 4I3 is about 226 miles. The third refueling stop was 2006 EDT at I34, for 13.62 gallons of 100LL. The distance between 4I3 and I34 is about 174 miles. The pilot planned to fly the remaining distance from I34 to FES—about 275 miles—in a single leg.

During the trip, the pilot communicated to his fiancé via text message that the airplane was experiencing a "small electrical problem," and estimated his ETA at FES would be about 2215 CDT, well after dark. He planned to activate the airport lighting system with a handheld VHF radio, but was unsure if the radio's battery would last the entire flight. He asked his fiancé to be on the north end of runway 10 with a flashlight pointed north to help vector the airplane in for landing. His fiancé reported that the airplane was landing from the north to runway 10, and that in addition to the flashlight she brought, the main hangar/office building had one outside light on at the time of the accident. She said the pilot made an attempt to land the "blacked out" Cessna, but due to the lack of runway light and exterior lighting on the aircraft she couldn't tell if the airplane touched down or not. The last text message from the pilot stated, "keep light on." After several minutes of not seeing or hearing the airplane, the fiancé tried contacting the pilot multiple times with no response. The fiancé contacted law enforcement about 30 minutes after the last text message was received.

According to the NTSB, the Jefferson County (Missouri) Sheriff's Office initiated a search for the missing airplane working with multiple ground and air assets. Data acquired from the cellular phones in the wreckage were used to help determine the search area. The wreckage was located by air assets in a tree-covered swamp, near the Plattin Creek, on September 21 about 0740 CDT. The wreckage was situated about one-quarter mile southeast of the departure end of runway 19 and about 440 feet above mean sea level. The airplane was equipped with a Pointer 3000 emergency locator transmitter (ELT), Technical Standard Order 91 (operating on 121.5/243.0 megahertz). The U.S. Air Force Rescue Coordination Center at Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida, reported no ELT signals were received by their monitoring systems from the accident airplane. No evidence of breaching was observed with the wings that held the fuel tanks. A total of about 2.25 gallons of fuel were extracted from both fuel tanks. The Cessna 150H pilot's operating handbook (POH) states that the maximum capacity for both fuel tanks is 26 gallons total (13 gallons in each tank). The POH further states that the usable fuel amount for all flight conditions is 22.5 gallons total and the unusable fuel amount is 3.5 gallons total. The U.S. Naval Observatory, Washington, District of Columbia, provided various sun and moon data for the day of the accident for FES. Sunset was 1902, and the end of civil twilight was 1928. Moonrise was 1656, and the moon transit was 2206. The phase of the moon was listed as, "Waxing Gibbous with 83% of the moon's civil disk illuminated.

New Aircraft

Recently a Lancair owner purchased a second Lancair. He and his nephew picked up the aircraft that was recently modified with a Garmin G3X and Vertical Power power distribution system. The new owner did not get a pre-purchase inspection, nor did he spend any significant time flying the aircraft and checking all systems out. On the flight home the aircraft fuel system was not reporting fuel quantity correctly so they stopped for fuel. They got under way for home as the sun was setting. Enroute, they experienced a total failure of the electrical system. The aircraft had a standby alternator; was that engaged? Fortunately, the moon was up and the sky was clear, however the panel was dark.

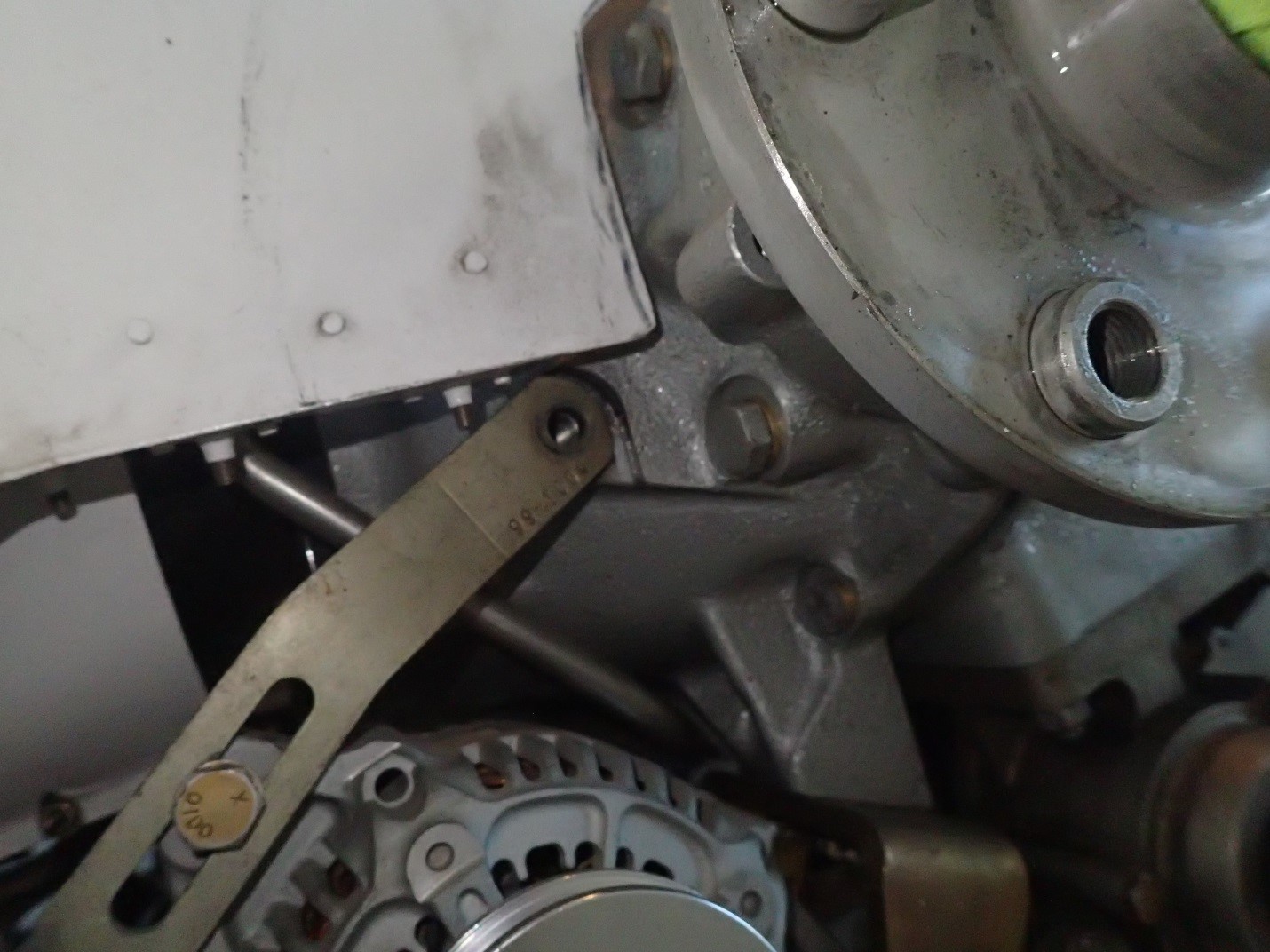

The pilot was familiar with the local area that they were now approaching and elected to land at a nearby airport using a handheld radio to communicate with tower. He was able to extend the landing gear via the alternate method, but could not confirm "down and locked" due to the total electrical failure. Unfortunately, the nose gear collapsed on touchdown, possibly due to an under-serviced gas strut on the nose gear. The pilot and his passenger were not injured, but their new purchase suffered some damage and will take some time and resources to repair. This was the second known accident this year involving a Lancair ferry flight home from an aircraft purchase. You may love the airplane but it does not necessarily love you back. What lessons may be learned of this experience? Would a pre-purchase inspection and shakedown flight—including emergency gear extension—have uncovered any issues with the aircraft, such as a deficient gas strut?

A post-accident inspection found the bolts securing the alternator had backed out because they were not safety-wired. Would a pre-purchase inspection have found that as well? Were there any self-imposed (job related) stresses? Is a night cross county flight in a “new-to-you,” unproven, experimental aircraft something you would do? What might have happened if the weather conditions were worse, say with an overcast layer or no moon? Perhaps spending the night at their stop would have been a better choice and reduced the possibility of a bad outcome.

Personal Minimums

LOBO recommends pilots stick to day VFR only until they have acquired 75-100 hours in a new aircraft. This ensures both you and the airplane are ready to tackle more challenging conditions. A lot of Lancairs and other GA aircraft are changing hands now with the improving economy. A wise pilot should plan to have a new purchase thoroughly inspected before flight. While that aircraft may look great in the photos online—is it really? All of the accidents and incidents reviewed here occurred at night or in poor weather. Think twice before tackling such conditions if you are not at the top of you game, and especially if you are inexperienced in the aircraft.

For questions/comments on this post contact Jeff via email: j.edwards [at] lancairowners.com.